Stefan Wesołowski (Interview)

Today we’re listening to Stefan Wesołowski, a Polish composer and multi-instrumentalist. He was born in Gdynia, grew up in Gdańsk, and took up the violin at an early age, inspired by his musical older brothers.1 He studied at the Academie Musicale de Villecroze, and has released solo work since the mid 2000s. His new record from June, Song of the Night Mists, is cinematic and imposing. On it, he plays violin, viola, cello, double bass, piano, and synths, often sampling his own recordings into novel constructions. His brother, Piotr, contributes pipe organ on the opus “Wilhelm Tombeau.” We’re also playing Liebestod, his 2013 solo LP, which features similar string arrangements and selective electronic elements. A conversation with Stefan follows the streaming links.

Song of the Night Mists - Stefan Wesołowski (37m, no vocals)

Spotify / Apple Music / YouTube Music / Amazon Music / Bandcamp / Tidal

Liebestod - Stefan Wesołowski (39m, no vocals)

Spotify / Apple Music / YouTube Music / Amazon Music / Bandcamp / Tidal

What's your earliest memory of music?

I believe my earliest musical memory is from when I was already in bed, or more precisely, lying in a pull-out bedding drawer in my sister’s room, which served as my makeshift bed. I must have been around four years old, and Kamila, my sister, was about fourteen. I was slowly drifting off to sleep while she sat at her desk, listening to her cassette tapes on a boombox. I can’t say with certainty what was playing at that exact moment – those evenings before sleep all seem to blur into one long soundscape in my memory, filled with Simon & Garfunkel, The Doors, The Police, or Clannad’s Legend. But the song that stands out the most, the one most deeply rooted in me, is “Golden Brown” by The Stranglers. Maybe that’s the very first memory.

There’s another formative moment that comes to mind, though I can’t say for sure if it came later, probably, since I could already read by then, though I’ve been reading for as long as I can remember. That memory is of our family singing “Gorzkie Żale (Bitter Lamentations)” during Lent. It’s a profoundly beautiful set of hymns focused on Christ’s passion and the sorrow of His mother, an absolutely unique tradition, deeply rooted in Polish Catholic spirituality. Faith was very much alive in our home. We prayed the Rosary together daily, and during Lent we’d sing “Gorzkie Żale.” So, in a way, my musical foundation is an amalgamation of these seemingly disparate experiences.

Who were the first artists that really inspired you and pointed you in your musical direction?

That’s a tough question – it really depends on how you define “inspiration.” On one hand, I could say that everything goes back to those “core memories” I just described. And if I had to point to what was most important and formative, it would probably be exactly that. But on the other hand, that alone wasn’t enough to push me toward composing, so maybe it doesn’t fully qualify as direct inspiration.

I clearly remember the moment I first felt the urge to compose. I was transcribing a 15th-century anonymous vocal piece, “Adoramus Te,” from the album El Cancionero de Montecassino, performed by La Capella Reial de Catalunya under Jordi Savall. Not long after, a Dominican friar I knew handed me some ancient Church Father texts and suggested I write music based on them. So I did, and, for some reason, it felt surprisingly natural, as if that creative impulse had just been waiting to be awakened. That’s when I realized that polyphonic vocal music and liturgical forms are, in a way, the roots of my own musical language.

Tell us about your journey with musical instruments – when you picked up each one, how, and why.

Let me make something clear from the start: yes, the album credits list me as playing a wide array of instruments, but in some cases, it's more about making sounds than truly playing them. With the double bass or cello, for example, I wouldn’t say I “play” them in the proper sense. I can coax some sounds out, but I’m not a trained player.

Keyboards are a different story. That’s just a basic skillset many musicians have, especially if they’re classically trained. So playing piano or synthesizers isn’t particularly noteworthy. But the violin – that’s my first instrument, and the one I’m most deeply connected to. I’m classically trained, and playing the violin feels as natural to me as reading or writing. Music has always been a native language to me, in large part because I was the youngest of six siblings, and three of my older brothers went through music school. My idol at the time was my eldest brother, Jacek, who played violin. I’m sure I pestered my parents to let me play just because he did. Jacek remained a part of my violin journey throughout my life, while I became a performing violinist, he became a luthier. When he moved to Poznań for high school and lived in a dorm, I would visit him and he’d sneak me into the prestigious Henryk Wieniawski Violin Competition through secret side entrances. Later, he built a violin for me that I played for years. When he moved to the U.K. to study and eventually began working at the famed J&A Beare workshop in London, he was in daily contact with some of the greatest instruments in the world. I remember him once emailing me: “Stefan, I have a Bergonzi in my hands – Charles Beare says it’s the best-sounding violin on the planet. Get on a plane.” The next morning, I was in London. They let me play that Bergonzi as much as I wanted. Jacek and I had lunch in a nearby park, and I flew back home to Gdańsk that evening. Sadly, Jacek died in a glider accident a few years ago. I miss him deeply. I’ve been feeling a growing urge to record a purely violin-based piece and dedicate it to him.

What was the setting in which you made Song of the Night Mists?

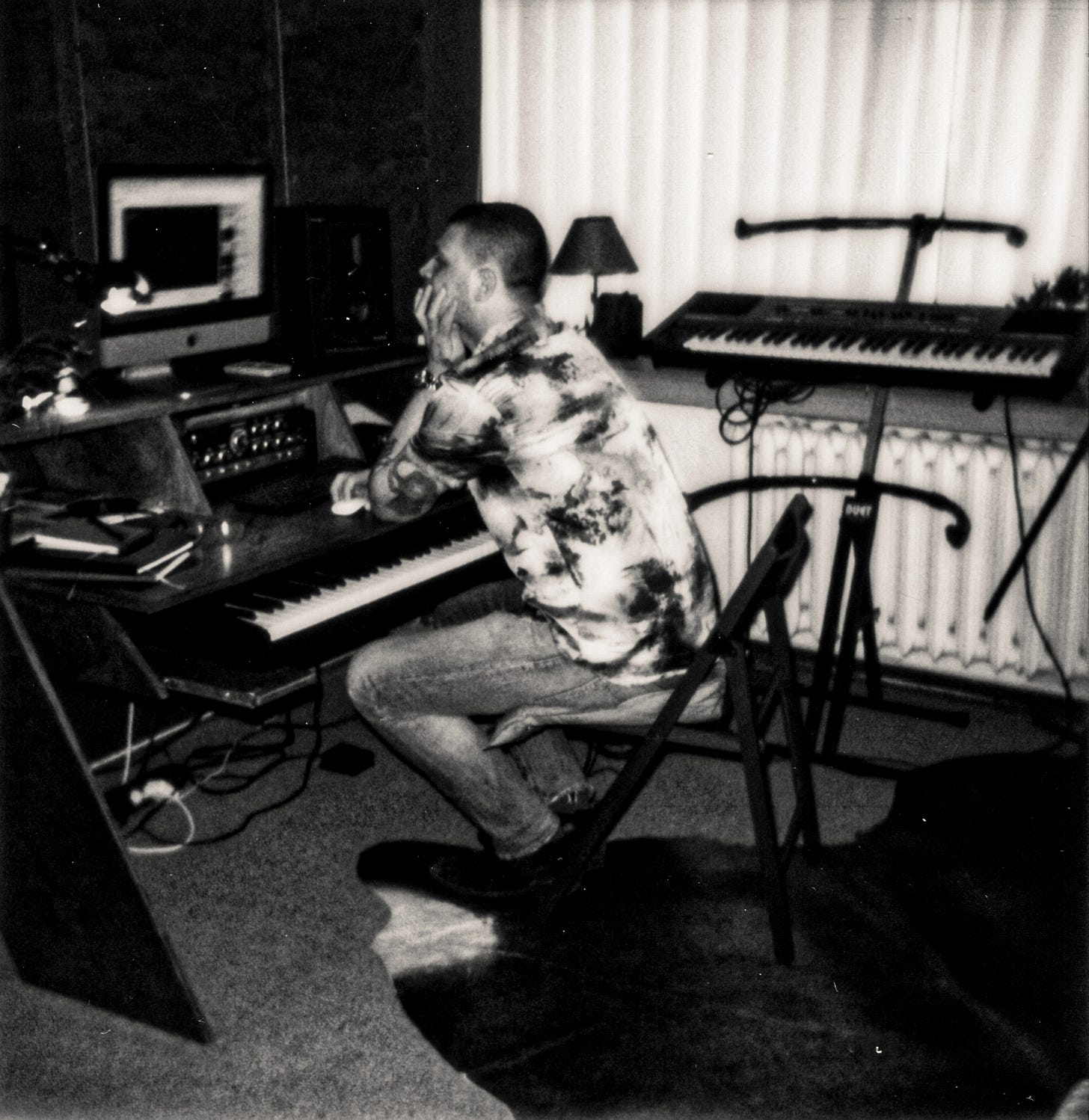

Song of the Night Mists is built from several interwoven layers, each interacting with the others in different proportions. I recorded a lot of acoustic instruments – violins, viola, cello, double bass, piano – some of which were later processed to various degrees. Maja Miro recorded the flute parts in my studio.

A big part of the album’s sound also comes from classic analog synthesizers, including the mighty Roland Jupiter-8 (an absolutely wild machine) and the Soviet-era Polivoks. I also used samples cut from 20th-century Polish compositions inspired by the folk traditions of the Tatra Mountains – pieces by Karol Szymanowski and Wojciech Kilar.

And then there's what’s become a bit of a personal tradition when I work on solo albums: I sample myself. As soon as I start feeling the direction of a new record, I dig through old sketches, snippets hiding in forgotten folders, and start reshaping them like clay to serve the new material. It always feels as though they were waiting in the wings for the right moment.

And then there’s the organ – a kind of rhetorical coda for the whole album. We recorded it at St. Nicholas’ Basilica in Gdańsk, which is also where I composed my very first polyphonic pieces. It’s a magnificent instrument with a glorious sound. And it was played by my brother Piotr, who is a professionally trained organist.

What are the differences between how you approach film scoring and how you approach your solo work?

Scoring a film can sometimes feel like torture, and other times like a playground. On one hand, film music is ultimately in service to something else, so I have to take direction, accept feedback, and revise my work, none of which is especially enjoyable for an artist. But on the other hand, film work takes some of the existential weight off. I don’t have to make grand statements or plant a flag artistically. It gives me the freedom to explore aesthetics I might not touch in my solo work.

My solo albums are something different entirely – they’re like an artistic credo, a statement of intent. They come out of me slowly. In fact, eight years passed between my last solo album and this one.

How do you discover new music these days? Any notable recent discoveries?

I have to admit, I don’t listen to a lot of new music. Between work and life, when I do get a rare moment to just sit and listen, I usually reach for something familiar – something I know will nourish me or help me reset. But of course, once in a while, something unexpected finds its way when someone recommends a track, or I catch something on the radio.

Not long ago, I was completely charmed by a group of Irish kids called Kabin Crew. They performed a live set on some radio show, one of the tracks was called “The Spark,” I think, and it just hit me. Totally wonderful.

Name an underrated artist from the past 50 years.

Oof, that’s a tough one. Honestly, it’d be easier to name a few overrated ones. Fifty years is a long stretch – enough time for several revolutions in global music. But if I had to name someone, I’d say in electronic music, Tim Exile is incredibly original and underrated. I’m not even sure if he’s still releasing records, but his work left a big impression on me.

In the more “serious” classical realm, Polish composer Paweł Szymański never really got the international recognition I believe he deserves. His work is extraordinary.

What are you working on next?

There are a few things in the works, but the biggest and most important project right now is a full-length opera I’m composing for the Baltic Opera in Gdańsk. It’s based on Weiser Dawidek, a novel by Paweł Huelle – a dreamlike, mysterious story about a Jewish boy in postwar Gdańsk, a city slowly rebuilding from devastation. The premiere is scheduled for March 2026.